![]() As a species, we hate cheaters. Just last month, I blogged about our innate desire to punish unfair play but it’s a sad fact that cheaters are universal. Any attempt to cooperate for a common good creates windows of opportunity for slackers. Even bacteria colonies have their own layabouts. Recently, two new studies have found that some bacteria reap the benefits of communal living while contributing nothing in return.

As a species, we hate cheaters. Just last month, I blogged about our innate desire to punish unfair play but it’s a sad fact that cheaters are universal. Any attempt to cooperate for a common good creates windows of opportunity for slackers. Even bacteria colonies have their own layabouts. Recently, two new studies have found that some bacteria reap the benefits of communal living while contributing nothing in return.

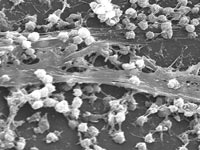

Bacteria may not strike you as expert co-operators but at high concentrations, they pull together to build microscopic ‘cities’ called biofilms, where millions of individuals live among a slimy framework that they themselves secrete. These communities provide protection from antibiotics, among other benefits, and they require cooperation to build.

Bacteria may not strike you as expert co-operators but at high concentrations, they pull together to build microscopic ‘cities’ called biofilms, where millions of individuals live among a slimy framework that they themselves secrete. These communities provide protection from antibiotics, among other benefits, and they require cooperation to build.

This only happens once a colony reaches a certain size. One individual can’t build a biofilm on its own so it pays for a colony to be able to measure its own size. To do this, they use a method ‘quorum sensing’, where individuals send out signalling molecules in the presence of their own kind.

When another bacterium receives this signal, it sends out some of its own, so that once a population reaches a certain density, it sets off a chain reaction of communication that floods the area with chemical messages.

These messages provide orders that tell the bacteria to secrete a wide range of proteins and chemicals. Some are necessary for building biofilms, others allow them to infect hosts, others make their movements easier and yet others break down potential sources of food. They tell bacteria to start behaving cooperatively and also when it’s worth doing so.

Filed under: Bacteria, Co-operation, Evolution, Health & Medicine | Tagged: Altruism, Bacteria, biofilms, cheaters, Pseudomonas, quorum sensing, selfishness | 5 Comments »